One of the most powerful tools in Theory of Constraints is the evaporation cloud. With a poetic name, it hides a robust technique for resolving conflicts. Whether between two individuals, two groups or simply to solve an internal dilemma, this tool dispels the fog. Without further ado, I explain the operation and technique through an example.

When to use the evaporating cloud?

It is a tool that makes the link between what to change and why to change visible. It is useful when two actions seem to exclude each other, or cannot be activated at the same time, although they tend to a common goal.

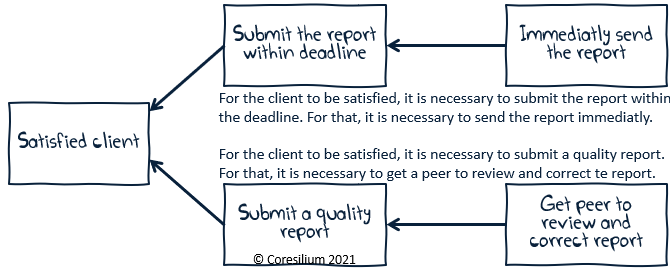

I have to deliver my report on time (action 1) and I have to deliver a quality document (action 2). I don’t have time to do both, and yet I have to satisfy my client (Common Goal).

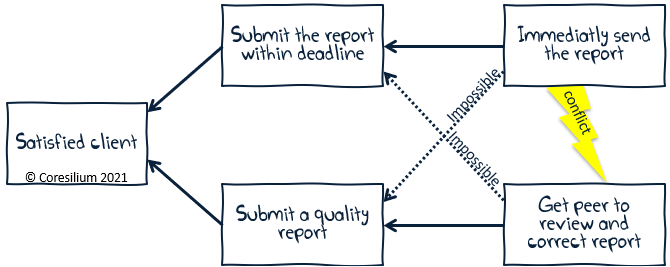

When it feels like compromise is impossible, we are in a win-lose, or worse, lose-lose situation. The evaporating cloud comes to find the win-win solution. It finds a solution that meets the common objective while ensuring that the conditions of each party are met.

Am I really in the presence of a conflict?

A conflict arises when I feel like I can’t enjoy the benefits of my choice. It’s totally subjective. Thus, for some choosing between cheese and dessert is a conflict, because they would like the sweet and the salty. For others it is not a conflict, because they have eaten enough and do not want anything sweet.

Concretely, you should observe conversations. Answers such as “All you’ve got to do is” or “yes, but” indicate a potential conflict.

In any case, by documenting the cloud, you will have confirmation that it is a conflict.

Documenting the conflict in an evaporating cloud

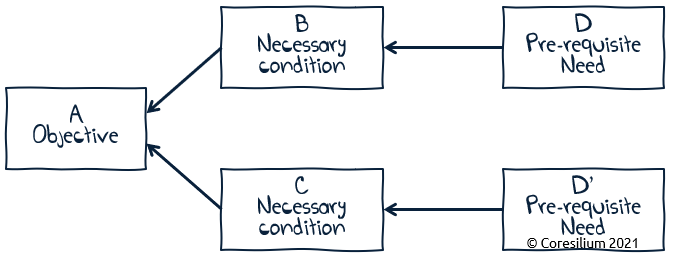

The evaporation cloud contains 5 boxes connected by arrows. You can make your cloud from right to left (“official” method) from left to right or vertically, depending on the space you have and your reasoning.

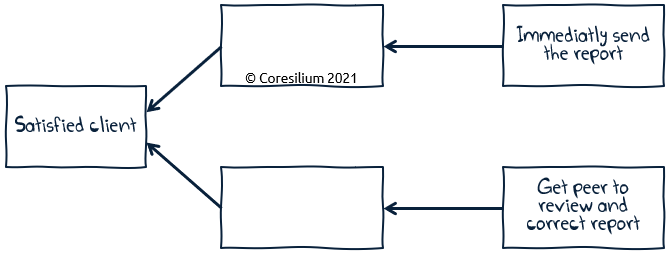

Step 1. Enter in boxes D and D’ the two terms of the conflict, the two contradictory actions or needs

Step 2. Write the common goal in box A.

Step 3. Look for the condition(s) needed for each branch. That is, what the person thinks it takes to achieve the goal. You can use a phrase to make sure you’ve placed each item in the right place. For (objective), it is necessary (necessary condition). For (necessary condition), it is necessary (prerequisite/need).

Step 4. Vérifiez que la condition C est mise en danger par le prérequis D et vice-versa. If this is not the case, there is no conflict, or the conditions are not the right ones, you have to keep looking (step 3)

Some tips

Whenever possible, you should be neutral. The two sides co-exist. There is no true or false at this point. You must lead participants to understand the impasse.

Try using affirmative mode for the common goal and the necessary conditions. It’s always easier to say what you don’t want, but it’s more useful to know what the person wants to get or have.

Resolving the conflict

Finally, you need to understand what is happening in the arrows. What are the assumptions, beliefs or principles that explain the connections between the boxes? By searching for links, with tools like the 5 Whys,new possibilities appear. Participants can understand the needs of others and find new solutions.

The author of the report cannot correct his own spelling mistakes.

Our client will no longer do business with us if there are spelling mistakes.

Our client will no longer do business with us if we deliver late…

In this case, a simple spell checker can solve the cloud and ensure on-time delivery with quick document review.

How to become good at conflict resolution?

As with everything, you have to practice… And you have to start easy. Do not strat by solving the conflict between your aunt and her neighbor who have not spoken to each other for 20 years… or to decide if you need to apply to a new position. This would be like skiing for the first time from the top of a black slope. Failure guaranteed…

Start by resolving simple internal conflicts such as choosing a dish at a restaurant. To stay in the theme, you can then resolve conflicts between individuals over the choice of restaurant or activity. Less emotionally charged conflicts will be easier to resolve because you will have access to assumptions, beliefs, or principles.

To go further

I saw more detailed evaporation clouds that add intermediate boxes. Whatever the tool, the practice will help you decide what works best for you and your organization. The goal is to understand the principle to use it intuitively.

Here is an example of a cloud with more boxes. It assumes that there is no easily identifiable common goal. Each of the columns represents one of the parts of the conflict. You will write down, from top to bottom, the goal that seems compromised or sacrificed, the problem, the inconvenience and the behavior. Ideally, you will be able to make the participants understand that they actually have a common goal, and you will be able to “reduce” the cloud to the first version that I presented to you.

If you are interested in this topic, I recommend reading two books. Behind the cloud by Jelena Fedurko, will bring you theoretical notions and techniques. Clarke Ching’s Corkscrew solution presents the tool in a romanticized way and is easier to read. The many examples help to understand the concepts and then use them.